Decade upon decade, there is a war being waged in the world of cameras that makes Kasparov v Karpov look like a fleeting squabble between two cuddly old lovers, and that war is Canon versus Nikon. And now just recently camera website LensRental decided to make a chess set out of the respective equipment to illustrate the point:

Updated every Monday, Wednesday and Friday ... and maybe other days too.

Sunday, July 31, 2011

Saturday, July 30, 2011

Every Picture Tells A Story: The Chess Gents of 1885

Number 16 in the series. This one by Martin Smith, with comment from Richard Tillett.

It is a happy coincidence that this episode of our series appears during the British Chess Championship in Sheffield as it focuses on another Congress held in another proud provincial city: Hereford, in 1885.

Thomas Leeming’s 1814 painting of the Gentlemen of Hereford Chess Club put Hereford on the chess map, and as we showed in our last but one episode (where you can also see the painting), it may commemorate one of the first ever provincial chess clubs in the country. Hereford may have had its ups and downs chess-wise ever since, but the Congress of August 1885 was a high point, with such stars as Bird and Blackburne in contention. It was as interesting then as maybe chess is now for goings-on off the board as much as on it.

One intriguing question for us was whether there was any connection between the Gents painted in the 1812 Chess Club and those involved in the Hereford Congress some 73 years later. There is a hint of a link. The second figure from the left in the painting is F. L . Bodenham, and in the list of patrons for the Congress was an F. Bodenham Esq.

You can see his name half-way down in the left hand column. This can’t be Francis Lewis himself, as he died in 1876, but might be his son, also called Francis, who was born in 1820. We can’t be sure, as Hereford was awash with Bodenhams, including a whole village so-named a few miles to the north. The reports of the Congress mention a key gofer (he “devoted himself with his usual zeal and ability”) Thomas Smith, the Secretary of the local Hereford Chess Association. So, in 1885, as in 1812, and as now, Hereford had its chess club.

You can see what an impressive list of patrons lined up to support the 1885 Congress, including the Lord Lieutenant of Hereford, the Mayor, a brace of Earls and a bevy of Lords and Knights. Even Robert Peel, Conservative M.P. for Huntingdon chipped in a £1 subscription. But behind this display of support there was much gentlemanly politicking.

The Congress was organised in the twentieth year of the Counties’ Chess Association, the moving spirit of which was the Reverend Arthur Boland Skipworth, himself a decent chesser.

The CCA aimed to represent and organise amateur chess in the provinces and was very much the Reverend’s creature. He was mightily displeased by the pretensions of the rival, upstart, London-based British Chess Association which proposed also to organise chess meetings in the provinces, being so bold, as it did in October 1885, also to offer federation, as if of equal standing. This impudent suggestion Skipworth swatted away, loftily deeming it unworthy to put before the members of the CCA, let alone discuss.

Over my dead body would your writ run in the counties, he was telling the BCA, and in 1885, his clerical duties notwithstanding, a grand gesture was the order of the day. So, as well as running his 290 acre farm with a staff of ten souls, administrating the CCA, sitting on the Council of the BCA (as a kind of Trojan Horse), and playing quite a bit of chess (e.g. he lost a match +2-5=0 to Bird that same year) and, one supposes, delivering the odd sermon or two, he and the CCA organised the Hereford Congress, playing himself and finishing 7th in a field of 11.

Skipworth’s (sorry, that should read “the CCA’s”) prospectus for the tournament invited “Chess Masters from the different parts of the world” to enter. The “munificence of Mr. Anthony of Hereford” (a local big-wig) would underwrite their prize money. But otherwise individuals and clubs the length and breadth of the land were invited to subscribe to provide prizes for the parallel amateur competitions. To which the Chess Monthly, the organ of the BCA, sniffily declared itself “greatly averse” to these appeals for funds to enable “a few amateurs to exhibit their skills at chess in some provincial town”. Ouch. Sheffield beware.

The venue for the Congress was Green Dragon Hotel in Hereford, which is still there today.

Here the management considerately provided “separate little tables” for the pairs of players, and even an office for writing letters, and a board for displaying results: declared to be “decided improvements” on previous arrangements.

An endearing feature of the Congress was a chess problem setting competition in which the entries were accompanied by “mottos”, the most bizarre of which was this cod French effort: “Pas delle yeux Rhone que nous”, and you are on your tod working out what that means. These bons mots were attached to this three-mover.

The line-up for the Masters tournament was shown in this photograph in the Illustrated London News:

There was evidently a need to make up the numbers in the “international” Masters by inviting a number of home-grown strong amateurs to take part, including the three Reverends, a point the BCA’s Chess Monthly seized on for another snipe at the CCA.

But the number of men of the cloth is interesting in itself. In fact, among the participants in the various competitions of the Congress, and the Patrons and subscribers lists there are no less than twenty-three clerics, of whom seven played in the tournaments. They used to say that the Church of England was the Tory Party at prayer; the Hereford Congress looked like the C of E at play, not heeding the charge that they might be neglecting their pastoral duties. No worries! Giving them his blessing was a most prestigious Patron: the Lord Bishop of Hereford.

As for the chess, the Masters was notable for the christening of 1.f4 as “Bird’s Opening” courtesy of the Hereford Times, which reported, on the 8th August, “Mr. Bird with his own opening” beating Mr. Pollock, and “Mr. Thorold with Bird’s Opening…defeated by Mr Blackburne”. Helping to give the Congress legitimacy as an international tournament was Herr Schallopp of Germany: according to the British Chess Magazine “a very fine player, and withal a very nice man. He won golden opinions during the tourney, and if he had won first prize, his victory would have been hailed with delight”. Alas, he finished second equal with Bird, but was the only player to beat tournament victor Blackburne with this effort.

However, he took his eye off the ball in his game with Mr. Thorold, who flew the flag for the English amateur and defeated him. One wonders what the “very nice man” said to Thorold for depriving him of first prize and his hail of delight. You'll find the game here.

This game and others were annotated in various places, invariably by the amateurs. In the British Chess Magazine the Reverend Ranken offered his thoughts on the Thorold v Schallopp encounter, suggesting that instead of 10…Be6 “we see no objection to taking the QP, which we do not think Mr.Thorold ought to have abandoned”. Hmmm. 10…Qxd4 11. Qb3+ Kg7 12. Qf7+ Kh6 13. Bxf4+ Kh5 14.h3 looks pretty tasty to me, and I’d be pleased if someone’s computer agreed.

References

A. B. Skipworth (ed). The Book of the Counties’ Chess Association, Hereford 1885. Originally London 1886. Reprint Moravian Chess Publishing House. Contains reports given by the officers of the CCA.

Hereford Chess Association. Hereford in 1885 . Hereford 1985. Limited Edition. – with extracts from the British Chess Magazine 1885. Edited by Les Collard and Peter Johnston. Thanks to Les for depositing two copies with the Institute of Leeming Studies. Thanks also to Ray Collett for his briefing on the Congress. The Chess Monthly, Vol VI Sept. 1884 - Aug 1885.

P. W. Sergeant. A Century of British Chess (1934)

Every Picture Tells a Story index

It is a happy coincidence that this episode of our series appears during the British Chess Championship in Sheffield as it focuses on another Congress held in another proud provincial city: Hereford, in 1885.

Thomas Leeming’s 1814 painting of the Gentlemen of Hereford Chess Club put Hereford on the chess map, and as we showed in our last but one episode (where you can also see the painting), it may commemorate one of the first ever provincial chess clubs in the country. Hereford may have had its ups and downs chess-wise ever since, but the Congress of August 1885 was a high point, with such stars as Bird and Blackburne in contention. It was as interesting then as maybe chess is now for goings-on off the board as much as on it.

One intriguing question for us was whether there was any connection between the Gents painted in the 1812 Chess Club and those involved in the Hereford Congress some 73 years later. There is a hint of a link. The second figure from the left in the painting is F. L . Bodenham, and in the list of patrons for the Congress was an F. Bodenham Esq.

You can see his name half-way down in the left hand column. This can’t be Francis Lewis himself, as he died in 1876, but might be his son, also called Francis, who was born in 1820. We can’t be sure, as Hereford was awash with Bodenhams, including a whole village so-named a few miles to the north. The reports of the Congress mention a key gofer (he “devoted himself with his usual zeal and ability”) Thomas Smith, the Secretary of the local Hereford Chess Association. So, in 1885, as in 1812, and as now, Hereford had its chess club.

You can see what an impressive list of patrons lined up to support the 1885 Congress, including the Lord Lieutenant of Hereford, the Mayor, a brace of Earls and a bevy of Lords and Knights. Even Robert Peel, Conservative M.P. for Huntingdon chipped in a £1 subscription. But behind this display of support there was much gentlemanly politicking.

The Congress was organised in the twentieth year of the Counties’ Chess Association, the moving spirit of which was the Reverend Arthur Boland Skipworth, himself a decent chesser.

The CCA aimed to represent and organise amateur chess in the provinces and was very much the Reverend’s creature. He was mightily displeased by the pretensions of the rival, upstart, London-based British Chess Association which proposed also to organise chess meetings in the provinces, being so bold, as it did in October 1885, also to offer federation, as if of equal standing. This impudent suggestion Skipworth swatted away, loftily deeming it unworthy to put before the members of the CCA, let alone discuss.

Over my dead body would your writ run in the counties, he was telling the BCA, and in 1885, his clerical duties notwithstanding, a grand gesture was the order of the day. So, as well as running his 290 acre farm with a staff of ten souls, administrating the CCA, sitting on the Council of the BCA (as a kind of Trojan Horse), and playing quite a bit of chess (e.g. he lost a match +2-5=0 to Bird that same year) and, one supposes, delivering the odd sermon or two, he and the CCA organised the Hereford Congress, playing himself and finishing 7th in a field of 11.

Skipworth’s (sorry, that should read “the CCA’s”) prospectus for the tournament invited “Chess Masters from the different parts of the world” to enter. The “munificence of Mr. Anthony of Hereford” (a local big-wig) would underwrite their prize money. But otherwise individuals and clubs the length and breadth of the land were invited to subscribe to provide prizes for the parallel amateur competitions. To which the Chess Monthly, the organ of the BCA, sniffily declared itself “greatly averse” to these appeals for funds to enable “a few amateurs to exhibit their skills at chess in some provincial town”. Ouch. Sheffield beware.

The venue for the Congress was Green Dragon Hotel in Hereford, which is still there today.

Here the management considerately provided “separate little tables” for the pairs of players, and even an office for writing letters, and a board for displaying results: declared to be “decided improvements” on previous arrangements.

An endearing feature of the Congress was a chess problem setting competition in which the entries were accompanied by “mottos”, the most bizarre of which was this cod French effort: “Pas delle yeux Rhone que nous”, and you are on your tod working out what that means. These bons mots were attached to this three-mover.

The line-up for the Masters tournament was shown in this photograph in the Illustrated London News:

Back row, l. to r. : Gunsberg, Thorold, Bird, Pollock, Smith (Sec. HCA), Schallopp, Owen, Skipworth.

Front row, l. to r. : Mason, Blackburne, Anthony (Pres. HCA), Mackenzie, Ranken.

The eagle-eyed reader will note (a) the absence of Dr Tarrasch, who withdrew at the last moment, claiming that the prize monies were too skewed in favour of the winner and didn’t provide enough for the runners up. But perhaps he just didn’t fancy meeting Blackburne again, having blundered to a 22 move defeat against him in the Hamburg tournament the month before, and (b) no less than three Reverend Gentlemen: Owen, Ranken and Skipworth.

There was evidently a need to make up the numbers in the “international” Masters by inviting a number of home-grown strong amateurs to take part, including the three Reverends, a point the BCA’s Chess Monthly seized on for another snipe at the CCA.

But the number of men of the cloth is interesting in itself. In fact, among the participants in the various competitions of the Congress, and the Patrons and subscribers lists there are no less than twenty-three clerics, of whom seven played in the tournaments. They used to say that the Church of England was the Tory Party at prayer; the Hereford Congress looked like the C of E at play, not heeding the charge that they might be neglecting their pastoral duties. No worries! Giving them his blessing was a most prestigious Patron: the Lord Bishop of Hereford.

As for the chess, the Masters was notable for the christening of 1.f4 as “Bird’s Opening” courtesy of the Hereford Times, which reported, on the 8th August, “Mr. Bird with his own opening” beating Mr. Pollock, and “Mr. Thorold with Bird’s Opening…defeated by Mr Blackburne”. Helping to give the Congress legitimacy as an international tournament was Herr Schallopp of Germany: according to the British Chess Magazine “a very fine player, and withal a very nice man. He won golden opinions during the tourney, and if he had won first prize, his victory would have been hailed with delight”. Alas, he finished second equal with Bird, but was the only player to beat tournament victor Blackburne with this effort.

However, he took his eye off the ball in his game with Mr. Thorold, who flew the flag for the English amateur and defeated him. One wonders what the “very nice man” said to Thorold for depriving him of first prize and his hail of delight. You'll find the game here.

This game and others were annotated in various places, invariably by the amateurs. In the British Chess Magazine the Reverend Ranken offered his thoughts on the Thorold v Schallopp encounter, suggesting that instead of 10…Be6 “we see no objection to taking the QP, which we do not think Mr.Thorold ought to have abandoned”. Hmmm. 10…Qxd4 11. Qb3+ Kg7 12. Qf7+ Kh6 13. Bxf4+ Kh5 14.h3 looks pretty tasty to me, and I’d be pleased if someone’s computer agreed.

We see no objection

to taking the QP.

In 1898 the Reverend Skipworth went to answer to his maker as to whether chess had claimed more of his attention than had his flock, and the Counties’ Chess Association died with him. The field was now left clear for a single national chess body, the British Chess Federation, which arrived in 1904. Chess politics has never been as decorous since.to taking the QP.

References

A. B. Skipworth (ed). The Book of the Counties’ Chess Association, Hereford 1885. Originally London 1886. Reprint Moravian Chess Publishing House. Contains reports given by the officers of the CCA.

Hereford Chess Association. Hereford in 1885 . Hereford 1985. Limited Edition. – with extracts from the British Chess Magazine 1885. Edited by Les Collard and Peter Johnston. Thanks to Les for depositing two copies with the Institute of Leeming Studies. Thanks also to Ray Collett for his briefing on the Congress. The Chess Monthly, Vol VI Sept. 1884 - Aug 1885.

P. W. Sergeant. A Century of British Chess (1934)

Friday, July 29, 2011

Sheffield 2011: four rounds in

The 2011 British Championships only opened a few days ago and yet by the end of today it will already be half over. That's life for you, I suppose. Blink and you've missed it.

I've barely had a chance to keep an eye on what's been going on, and when I scanned the lists of the entrants to Championship tournament, I was surprised to see half-a-dozen people that I'd played before. Most of these - Peter Lalic, Yang-Fan, George Salimbeni and Sarah Hegarty I met when they were much younger, and less strong, than they are now, but there are a couple of exceptions. One is Ravia Haria, who I played at the Gatwick Open just a couple of months ago and the other is Chino Atako.

I first crossed pawns with Chino at the Dutch Opening theme tournament that Simon Williams organised in Hastings at the begining of 2010 to celebrate the launch of his first DVD. As I recall he - Atako - played the Staunton Gambit against me, an eminently appropriate choice for somebody with his name, and gave me a good, if mercifully short, leathering (I mentioned the game in passing here).

The next and only other time our paths crossed was April of this year when we found ourselves on board seven of a Streatham & Brixton v Redhill Surrey League match. Funny to think that at as I write these words the person I played in that mundane club game is busy preparing himself for a clash with last year's British Champion and current world number 28, Mickey Adams. That is, nevertheless, exactly what is happening and Chino richly deserves his chance, having scored an excellent 2.5 points (wins against Ronan Magee and FM Laurence Webb, a draw against IM Andrew Ledger) from the first three rounds.

I'm not a big fan of the current format of the championship tournament, but it's certainly true that one of the strengths of the event is that every now and again it gives (if he will forgive me for the term) 'ordinary' club players like Chino a chance to take a pop and one of the big guns. The problem is that this feature of the tournament comes at a price and ultimately, although not only because of games like Atako-Adams, we risk the title being determined not by games played between the leading contenders, but rather by a comparison of how the top players score against the rest of the field. This wouldn't matter so much if the contenders played similar opposition, but often they do not.

IM Simon Ansell wrote on the EC Forum yesterday morning (as part of a discussion about the Accelerated Pairing rules that are being used),

... any system that, barring an exceptional set of results (there haven't been), results in the top two seeds on the same score playing two opponents 400 points apart, is fundamentally flawed imo

which seems hard to argue against. Similarly, if we're looking at discrepancies in how the pairings turn out, we might also point to the fact that IM Sue Lalic has played four Grandmasters while the GMs themselves have, for the most part, only had to take on one of their brothers thus far. Nosher (Conquest, Summerscale) and Conquest (Short, Jones) have played two each, it's true, but that is more than offset by Williams, Wells and Pert not yet having played any.

As Chris Kreuzer said on that same EC Forum thread,

With 12 GMs in the field, you would hope the leading GMs after 11 rounds would have played at least 7-8 other GMs *

and once again it's impossible to disagree with the sentiment. Once the tournament is over, an analysis of the number of all-GM clashes, the number of times that the people who placed first to tenth played the other top ten finishers and, in particular, the number of games that Adams, Short, Howell and The Corporal play against each other will go a long way to demonstrating how good at selecting a champion the current tournament actually is. Based on previous years, "not especially" is my guess.

Anyhoo, if we have doubts about the nature of the tournament it is perfectly possible to express them while also celebrating Chino Atako's achievement so far and the opportunity to play Mickey Adams that he has secured as a result. It is a huge slice of good fortune for him, perhaps, but certainly no fluke - witness, for example, the unbeaten 3.5/5 (including a draw with Simon Williams) that he scored at the Gatwick tournament mentioned above - and I wish him all the best for the game.

[UPDATE: Thursday pm.

The game has now been played - and, needless to say, with the expected result. Still, I hope that Chino enjoyed his moment in the spotlight nevertheless.]

Photographs from the Championship Website

* Chris continued: "Though that depends on the GMs playing like, well, grandmasters", which is an entirely reasonable addendum.

Thursday, July 28, 2011

When will they ever learn?

I was surprised to learn, from his Twitter feed, that Ray Keene had been invited to open the 2011 British Chess Championships.

I was surprised for a number of reasons, most of which I'll not go through here on the assumption that they are long since over-familiar to readers. Still, I might just mention that to my recollection, Ray resigned from what was then the BCF, over twenty years ago, rather than repay money he was accused of acquiring illegitimately. (As I recall he then went on to set up a rival, the English Chess Association, membership not very much more than one.)

So one assumes that this is now all settled and the money has been repaid. Otherwise it's kind of hard to understand how come Ray was standing in front of the competitors before the Championships

[Image: Andrew R. Camp]

giving an opening speech, before heading back to London with great satisfaction

conceivably at having got away with it once again.

What's odder still about this business is the absence of any reference to it on either the Championships website or that of the English Chess Federation. I mean who invites somebody to open their premier event - and then leaves that totally unmentioned? One might as well forget to mention the sponsor's name.

So you'd think we would have a piece saying "the Championships were opened today with speeches from the President, CJ de Mooi, and Raymond Keene OBE, columnist for the Times and the Spectator and author of several hundred chess books". Strangely, though, we don't. They keep it low-key. So low-key, it's basically invisible.

What's all this about? Lord knows, though it's not the first time that Ray has been a great deal more heavily involved with the ECF than CJ de Mooi has been prepared to admit. But the two of them seem to be quite the mutual admiration society, even if on CJ's part it's deemed politic to keep quiet about his half of the admiration. However you describe it, though, it seems clear that the two of them are on very good terms.

It's my view that, at the very best, this shows very poor judgement of the part of CJ de Mooi, since he's the President of the English Chess Federation and Ray Keene has a thirty-year record of ripping off other people in chess, English and otherwise. Put simply, the association, between our President and Ray Keene, is a tawdry one.

Still, y'know, Ray gives a lot of publicity to chess (or at least his Times column does) and he's raised a lot of money in the past though sponsorship and - like Kirsan - he's never been convicted or anything and yadda yadda yadda. I know how that routine goes and I'm not going to engage with it. Partly because I'm not going to engage with an argument that says that ethics don't matter if somebody might wave some money at you or give you some publicity. Partly because I know from long experience that it's just not worth it.

I'll just say two things that I have said before, and which, no doubt, I shall have occasion to say again. The first is that the reason Ray has got away with it for so long is that people have been prepared to let him get away with it. They've done so precisely because of an absence of ethics, a preparedness to look the other way, to pretend and mumble and say well-it's-never-actually-happened-to-me, which is an identifiable feature of English chess. It's been going on too long for any other view to make much sense. English chess accepts Ray Keene because - to an extent, too great an extent - what he is like, is only what English chess is like. Writ large. Writ very large.

The second, of course, is that as long as English chess tolerates Ray Keene, it has no business complaining about Kirsan Ilyumzhinov. Because Kirsan Ilyumzhinov is just Ray Keene. Writ larger. Writ figuratively larger.

[Ray Keene index]

[Thanks to Jonathan and Angus]

Wednesday, July 27, 2011

Soviet chess grandmaster seeks asylum in Holland after Moscow criticism

Click for a closer look

(click again when you get there for a very close look)

The Times

Wednesday July 28th 1976

Soviet chess grandmaster seeks asylum in Holland after Moscow criticism

From Our Correspondent

The Hague, July 27

Viktor Korchnoi, aged 45, the Soviet chess player, has asked for political asylum in the Netherlands, the Dutch Ministry of Justice said today.

He has been in the country for the past three weeks competing in the annual IBM chess tournament, in which he shared first place with Britain’s Tony Miles. Korchnoi, whose whereabouts are being kept secret, has been granted a temporary residence permit, and a decision on his request will probably be reached within two weeks.

Jan Hein Donner, one of the Dutch competitors in the IBM tournament, said that many of the other competitors knew of Korchnoi’s intention to defect.

“Life has become impossible for him in the Soviet Union since he criticized world champion Anatoly Karpov”, Donner added. “He was subjected to increasing criticism and nuisance from both the Soviet Chess Federation and the authorities in general. He had been thinking about defecting for some time. I told him exactly how to go about it.”

Korchnoi’s family, including his wife and 17-year-old son, are still in the Soviet Union. He has frequently visited Holland, as well as many other Western countries, to play in tournaments.

Harry Golombek writes: The news of Korchnoi’s defection will come as no surprise, since of all the Soviet grandmasters he was the most outspoken in his condemnation and even ridicule of attempts made by Moscow’s ideologists to influence the world of chess.

But his decision represents a serious loss to the Russians. With Bobby Fischer no longer active, Korchnoi ranks as second in the world to the champion Karpov. His style of play reflects his personality – dynamic, independent and to a large extent original.

Tony Miles, the British grandmaster, said that at one stage in Amsterdam, Korchnoi asked him how to pronounce the word “asylum”, which gave him a shrewd idea of what might take place.

Moscow: Korchnoi’s wife Bela said from her home in Leningrad that she was surprised at her husband’s decision. She was awaiting a call from him. – AP

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

Opening questions

The following passage was written about an opening variation which appeared in the first half of the current Dortmund tournament.

b. Who wrote the passage?

c. Where was it written?

[Chessbase Dortmund round reports: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Although he used it four times, drawing all fours games in short order, I still consider this a difficult variation for Black. Smyslov had to display a great deal of resourcefulness in order to equalise, and his opponents did not always exploit their opportunities to the fullest. After this tournament, neither Smyslov nor the other masters made much further use of this defence, so it has disappeared from practice.a. In which game from Dortmund did it appear?

b. Who wrote the passage?

c. Where was it written?

[Chessbase Dortmund round reports: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Monday, July 25, 2011

Chesserettes

Previously at Benasque 2011:

There seemed to be quite a few lady people playing in Benasque. I mention this not because it's a bad thing - it obviously isn't - nor even because it's a good thing - although, for various reasons that shan't detain us today, it seems to me that it is - but simply because I noticed it. Actually, the really noticeable thing was not so much that there were lots of females at the tournament per se, but the fact that for the most part they were adults and not girls.

Women in their twenties and older. It's a constituency of chessers that barely exists in England and yet in Spain it's one that seems to be flourishing. OK, there were over 440 players in Benasque so you'd expect to see more females there than at an event like Gatwick where there were 'only' 156 of us, but it seemed to me that not only were there more in Benasque in absolute terms, there were more proportionally too.

As it happens I played two women during my fortnight in Spain: Leticia Pardo Simon in the fourth round and WIM Roquelina Fandino Reyes in the tenth. By way of comparison, I'd had just one female opponent in more than 140 rated games in England between September 2007 and leaving for Benasque at the beginning of July (Julie Korseva in the first round at Sunningdale in May of this year) and off the top of my head I can only remember facing two other women over the board* going back a decade more.

It's not so unusual to see girls (by which I mean under 12s or thereabouts) at the Richmond Rapidplay, say, or Golders Green (I played Akshaya Kalaiyalahan at Adam Raoof's tournament last February), but adult females in club or tournament chess are a different story. Not completely unheard of, for sure - over the last couple of seasons my own club has received visits from Susan Lalic and Natasha Regan playing for, if I recall correctly, Ashtead and Redhill respectively - but certainly much more of a rarity.

Consider the field in Sheffield, for example. At the time of writing 5 of 85 entrants to the Championship itself (5.88%) are women which, although up from last year's 3 of 78 (3.84%), is hardly substantial and while I haven't checked the subsidiary tournaments my guess is that the proportion of women in those events will be even smaller.

Large numbers of women just aren't playing chess in Britain just now and yet they do seem to be in Spain. Well, larger numbers than here, at least. Either way, it's an interesting discrepancy, don't you think? I don't know how to explain it, and I don't know how to 'fix' it - other than to mention in passing that e2e4 going out of their way to attract women to their events is a praiseworthy initiative - but I can at least notice it. That will have to do for now.

PS:

In both of the games mentioned I drew from a winning position. I seem to remember reading in an Bill Hartston column that when giving a simul Anatoly Karpov would concede draws when playing against a woman because he considered it to be the chivalrous thing to do. I, on the other hand, did it because I'm incompetent.

* Anna Partington and Jane Seymour both of which must have been getting on for ten years ago. I did play Sarah Hegarty in the Coulsden minor back in 2000, but she was only ickle then, so that doesn't count. Incidentally, I could remember all these names without having to look them up which says quite a bit about how infrequently I've had women opponents in the past.

They're Off

The British Chess Championships begin in Sheffield today. You probably already know that. This is just a quick post to let you know that we haven't forgotten.

We'll be starting the week finishing up with our memories of Benasque, and then on Wednesday we'll be celebrating the anniversary of one of the most important events in 20th century chess. Our coverage of the British will kick in as week one comes to an end.

We'll be starting the week finishing up with our memories of Benasque, and then on Wednesday we'll be celebrating the anniversary of one of the most important events in 20th century chess. Our coverage of the British will kick in as week one comes to an end.

Sunday, July 24, 2011

Saturday, July 23, 2011

Every Picture Tells A Story: Ian Greenlees - What A Tease

Number 15. This one by Martin Smith, with ideas and comment by Richard Tillett.

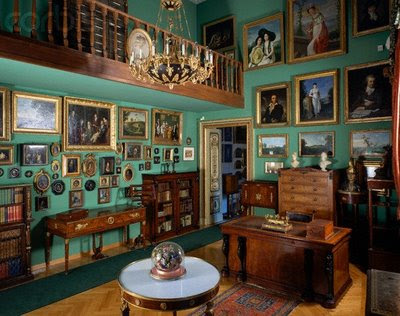

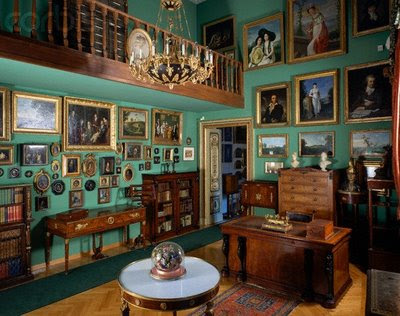

This series has gone on longer, and in more extraordinary directions, than we ever expected when posting the first episode in October last year. It was Mario Praz who kicked off our search for the Gentlemen of Hereford Chess Club with his (reversed) illustration, item 139, in An Illustrated History of Interior Design: From Pompeii to Art Nouveau (1964 reprinted 1982). We then thought we could track the picture down through the Ian Greenlees Collection which Praz gave as the source of his image.

But Greenlees had died in 1988 and his collection dispersed. We hoped that from beyond the grave he might lead us to the picture, but it was not to be. Although we found two more versions of the picture along the way we didn’t get any nearer to the one that once hung on Greenlees’s wall. Instead, we got another picture: that of Ian Greenlees and the company he kept. It’s worth a look, and we crave your indulgence in what follows, because although the Greenlees story is interesting in itself, there’s precious little chess, and not much either of the Gents of Hereford.

But Greenlees had died in 1988 and his collection dispersed. We hoped that from beyond the grave he might lead us to the picture, but it was not to be. Although we found two more versions of the picture along the way we didn’t get any nearer to the one that once hung on Greenlees’s wall. Instead, we got another picture: that of Ian Greenlees and the company he kept. It’s worth a look, and we crave your indulgence in what follows, because although the Greenlees story is interesting in itself, there’s precious little chess, and not much either of the Gents of Hereford.

Greenlees was born in 1913 into a family with a profitable whisky distillery, whose fortune he later inherited. After a good Catholic education at Ampleforth College he got a First in Italian at Magdalen College, Oxford and in 1934 started teaching English Literature at the University of Rome under our Mario Praz (so they knew each other well ). In 1939 he was appointed Director of the British Institute in Rome, and when Italy entered the war in June 1940, Greenlees, only 27 years old, heroically led his staff across war-torn France to safety in London.

Now in the Army, he was made responsible for Italian-language propaganda broadcasts, took part in the Allied landing in North Africa and, when Fascist Italy conceded an armistice, was despatched across Italy (still infested with German patrols) to take command of a free radio station in Bari, in the heel of Italy, from where anti-fascist broadcasting was organised. By 1943 he had risen to the rank of Major.

The only photo we have found of Greenlees is the war-time snap above (or what remains of it), but there is also the suggestive comment by Australian author Shirley Hazzard that, in addition to being a friend of Graham Greene, he was “in appearance, manner, and pallor, a ringer for Sydney Greenstreet” who played Signor Ferrari in the noir-ish 1942 film Casablanca. Chess addicts will know it as the film in which Humphrey Bogart famously played chess, although not with the Greenlees doppelganger.

From 1947 to 1954, Greenlees was working for the British Council in Rome, but we’d like to make clear that any suggestion that the British Council was a front for espionage is, of course, highly fanciful. Highly fanciful. His title was “Assistant Press Attaché”. Perhaps we might have expected that a man mentioned in despatches, and with his knowledge of Italy, would be assigned a more elevated post, so we can only speculate as to his actual role, but with the ominous strength of the Italian Communist Party in the aftermath of the war, what better place to install an Italian speaking one-time Major of the British Army with the ear of leading Italian leftists.

So, for the next seven years Greenlees was rubbing shoulders with the Italian cultural elite, and possibly many others besides. Among them was Mario Praz, still Professor of English Literature at the University of Rome right through to 1966 (he was a staunch Anglophile, made a KBE in 1962).

In a career break between 1954 and 1958 Greenlees found time to write several articles, and a booklet on the well-nigh forgotten fugitive English ex-pat novelist and travel writer Norman Douglas, who lived and died in Capri, his memorable death-bed wish being (expletive deleted) “keep those f***ing nuns away from me”. In 1958 Greenlees was appointed Director of the British Institute in Florence, where he remained until 1981, and is credited with expanding its role and influence, assisted ably by none other than Antony Blunt, the other Cambridge spy, who was on its Board of Governors. What a thought: Antony Blunt, Surveyor of the Queen’s pictures, connoisseur of French painting and architecture, expert in Italian art, and sometime traitor, taking a wee dram chez Greenlees and casting his discerning eye over Leeming’s Gents of Hereford Chess Club.

During his tenure Greenlees was an occasional letter writer to the Times: appealing for aid to help victims and save artworks during the floods in Italy in 1966, and campaigning to preserve the traditional form of the Catholic Mass in 1971 (with co-signatories Agatha Christie and Graham Greene, among many others). He also helped create the Italian version of the RSPB which eventually won a ban against the slaughter en masse of migrating songbirds.

He dabbled in the London auction houses, with several sales in the 1960s, including 21 lots of Chinese ceramics and nine lots of modern English pictures at Sotheby’s in 1961, of which three were Sickerts.

Somehow or other, probably at an auction house or through a dealer, he came by the Gents of the Hereford Chess Club, which was sold on in 1991, a few years after his death. He accumulated a huge library which, combined with that of his friend Robin Chanter (“a brilliant and dissolute figure” ), totalled 28,000 books. It was housed in the mansion in Bagni di Lucca in Northern Italy which they bought together in 1969, and they wintered in Capri, Douglas’, Greene’s and food-writer Elizabeth David’s watering hole.

Chanter however set up home with Ms Laura Buchan (grand-daughter of John "Thirty-Nine Steps" Buchan) in 1975, though they week-ended with Greenlees, and in the 1980s all three lived together in Bagni di Lucca. After Greenlees died in 1988, the library was donated to the local Commune, and Robin Chanter died in 1999.

Our trawl through the life of Ian Greenlees OBE has disappointingly shed no light on the whereabouts of the version of the Gents of Hereford Chess Club once in his possession. Until we turn it up some other way we will let him tease us no more.

But we have got to know Greenlees quite well. His Who’s Who entry listed his interests as swimming, walking and talking, but not, alas, playing chess. His Times obituary said “He was an unambitious man but he mastered the art of being happy and knew how to impart this gift to others. He hated war, the army, nationalism and public schools.” And was perhaps, in no particular order: tinker, tailor, soldier, spy?

Acknowledgements and Sources

Thanks to Jonathan B., and Richard Rawles for their help with research for this post; and to James Buchan and his sister for answering my query on the Guttuso portrait, albeit in the negative.

Simona Tobia's Advertising America; The United States Information Service in Italy (1945-56) describes Greenlees involvement with Radio Bari.

See Alfred de Grazia’s Autobiography A Taste of War for Greenlees activities in war time Italy, his army liaison with the American forces, and a description of him as a “gay type”. Graza gives the photograph of Greenlees.

This series has gone on longer, and in more extraordinary directions, than we ever expected when posting the first episode in October last year. It was Mario Praz who kicked off our search for the Gentlemen of Hereford Chess Club with his (reversed) illustration, item 139, in An Illustrated History of Interior Design: From Pompeii to Art Nouveau (1964 reprinted 1982). We then thought we could track the picture down through the Ian Greenlees Collection which Praz gave as the source of his image.

But Greenlees had died in 1988 and his collection dispersed. We hoped that from beyond the grave he might lead us to the picture, but it was not to be. Although we found two more versions of the picture along the way we didn’t get any nearer to the one that once hung on Greenlees’s wall. Instead, we got another picture: that of Ian Greenlees and the company he kept. It’s worth a look, and we crave your indulgence in what follows, because although the Greenlees story is interesting in itself, there’s precious little chess, and not much either of the Gents of Hereford.

But Greenlees had died in 1988 and his collection dispersed. We hoped that from beyond the grave he might lead us to the picture, but it was not to be. Although we found two more versions of the picture along the way we didn’t get any nearer to the one that once hung on Greenlees’s wall. Instead, we got another picture: that of Ian Greenlees and the company he kept. It’s worth a look, and we crave your indulgence in what follows, because although the Greenlees story is interesting in itself, there’s precious little chess, and not much either of the Gents of Hereford.Greenlees was born in 1913 into a family with a profitable whisky distillery, whose fortune he later inherited. After a good Catholic education at Ampleforth College he got a First in Italian at Magdalen College, Oxford and in 1934 started teaching English Literature at the University of Rome under our Mario Praz (so they knew each other well ). In 1939 he was appointed Director of the British Institute in Rome, and when Italy entered the war in June 1940, Greenlees, only 27 years old, heroically led his staff across war-torn France to safety in London.

Now in the Army, he was made responsible for Italian-language propaganda broadcasts, took part in the Allied landing in North Africa and, when Fascist Italy conceded an armistice, was despatched across Italy (still infested with German patrols) to take command of a free radio station in Bari, in the heel of Italy, from where anti-fascist broadcasting was organised. By 1943 he had risen to the rank of Major.

Ian Greenlees, on the left, in Naples 1943.

Greenlees crops up in the second world war reminiscences of Alfred de Grazia. Sharing his thoughts on male-bonding and homosexuality among troops in the US and British armies, de Grazia refers to Greenlees as a “gay type”. He never married, and you can speculate, as you look at the beefcake on display in the Gents of Hereford, and the masochistic ectasy of Saint Sebastian on the wall, whether this orientation may have influenced his taste in art.

The object of the male gaze?

Referring to Greenlees’ role in intelligence operations later in the war, his Times obituary says “he was one of the leading lights in the famous intelligence unit at Via Po where all the important Italian politicians…were entertained”. Greenlees went on to represent Britain in negotiations in Italy to establish a new government purged of Fascist influence, and in the immediate post-war period he was well acquainted with the main players vying for influence in a free Italy, including Togliatti, the leader of the Italian Communist Party.The only photo we have found of Greenlees is the war-time snap above (or what remains of it), but there is also the suggestive comment by Australian author Shirley Hazzard that, in addition to being a friend of Graham Greene, he was “in appearance, manner, and pallor, a ringer for Sydney Greenstreet” who played Signor Ferrari in the noir-ish 1942 film Casablanca. Chess addicts will know it as the film in which Humphrey Bogart famously played chess, although not with the Greenlees doppelganger.

“A ringer for Sydney Greenstreet”

with Bogey (chess grade estimated at ELO 2100).

From 1947 to 1954, Greenlees was working for the British Council in Rome, but we’d like to make clear that any suggestion that the British Council was a front for espionage is, of course, highly fanciful. Highly fanciful. His title was “Assistant Press Attaché”. Perhaps we might have expected that a man mentioned in despatches, and with his knowledge of Italy, would be assigned a more elevated post, so we can only speculate as to his actual role, but with the ominous strength of the Italian Communist Party in the aftermath of the war, what better place to install an Italian speaking one-time Major of the British Army with the ear of leading Italian leftists.

So, for the next seven years Greenlees was rubbing shoulders with the Italian cultural elite, and possibly many others besides. Among them was Mario Praz, still Professor of English Literature at the University of Rome right through to 1966 (he was a staunch Anglophile, made a KBE in 1962).

Mario Praz KBE (1896-1982) at home.

[A dead ringer for Lord Clark of Civilisation]

The Scrivania at Mario Praz’s Palazzio

Getting back to our subject, Greenlees was also friends in the 50s with Renato Guttuso, a committed anti-Fascist artist who was later to be elected a Senator for the Italian Communist Party. Tantalisingly, in 1950 he painted Greenlees' portrait in army uniform which, frustratingly, we have not been able to trace.In a career break between 1954 and 1958 Greenlees found time to write several articles, and a booklet on the well-nigh forgotten fugitive English ex-pat novelist and travel writer Norman Douglas, who lived and died in Capri, his memorable death-bed wish being (expletive deleted) “keep those f***ing nuns away from me”. In 1958 Greenlees was appointed Director of the British Institute in Florence, where he remained until 1981, and is credited with expanding its role and influence, assisted ably by none other than Antony Blunt, the other Cambridge spy, who was on its Board of Governors. What a thought: Antony Blunt, Surveyor of the Queen’s pictures, connoisseur of French painting and architecture, expert in Italian art, and sometime traitor, taking a wee dram chez Greenlees and casting his discerning eye over Leeming’s Gents of Hereford Chess Club.

During his tenure Greenlees was an occasional letter writer to the Times: appealing for aid to help victims and save artworks during the floods in Italy in 1966, and campaigning to preserve the traditional form of the Catholic Mass in 1971 (with co-signatories Agatha Christie and Graham Greene, among many others). He also helped create the Italian version of the RSPB which eventually won a ban against the slaughter en masse of migrating songbirds.

He dabbled in the London auction houses, with several sales in the 1960s, including 21 lots of Chinese ceramics and nine lots of modern English pictures at Sotheby’s in 1961, of which three were Sickerts.

Somehow or other, probably at an auction house or through a dealer, he came by the Gents of the Hereford Chess Club, which was sold on in 1991, a few years after his death. He accumulated a huge library which, combined with that of his friend Robin Chanter (“a brilliant and dissolute figure” ), totalled 28,000 books. It was housed in the mansion in Bagni di Lucca in Northern Italy which they bought together in 1969, and they wintered in Capri, Douglas’, Greene’s and food-writer Elizabeth David’s watering hole.

Chanter however set up home with Ms Laura Buchan (grand-daughter of John "Thirty-Nine Steps" Buchan) in 1975, though they week-ended with Greenlees, and in the 1980s all three lived together in Bagni di Lucca. After Greenlees died in 1988, the library was donated to the local Commune, and Robin Chanter died in 1999.

Our trawl through the life of Ian Greenlees OBE has disappointingly shed no light on the whereabouts of the version of the Gents of Hereford Chess Club once in his possession. Until we turn it up some other way we will let him tease us no more.

But we have got to know Greenlees quite well. His Who’s Who entry listed his interests as swimming, walking and talking, but not, alas, playing chess. His Times obituary said “He was an unambitious man but he mastered the art of being happy and knew how to impart this gift to others. He hated war, the army, nationalism and public schools.” And was perhaps, in no particular order: tinker, tailor, soldier, spy?

Acknowledgements and Sources

Thanks to Jonathan B., and Richard Rawles for their help with research for this post; and to James Buchan and his sister for answering my query on the Guttuso portrait, albeit in the negative.

Simona Tobia's Advertising America; The United States Information Service in Italy (1945-56) describes Greenlees involvement with Radio Bari.

See Alfred de Grazia’s Autobiography A Taste of War for Greenlees activities in war time Italy, his army liaison with the American forces, and a description of him as a “gay type”. Graza gives the photograph of Greenlees.

Greenlees' booklet on Norman Douglas was published in 1957, No 82 in the Writers and Their Work series by the British Council and Longmans. His "nuns" quote comes from his Wikipedia entry.

Greenlees' obituary by Lord Hastings was in the Times, 2nd August 1988.

Robin Chanter's obituary by James Buchan is here.

Friday, July 22, 2011

Benasque 2011 : Streatham and Brixton against the grandmasters

The highest-finishing English player at Benasque was actually Jana Bellin, who finished with 6.5/10, the same score as Erik Teichmann but a few places higher on tie-break. I finished on a lousy 5/10, my tournament having the opposite trajectory to Jonathan's but a similar one to most of my games, in that I started well but went downhill from there.

During the first half, though, I played two grandmasters, while Angus, who was the best of our party with 6/10, played one. We scored, you'll not be astonished to hear, 0/3 in these games. But maybe it didn't have to be that way.

The first of these games was played in round two, in which I had the black pieces against Indian GM Neelotpal Das.

At first sight it's a fairly straightforward stronger v weaker player crush, which is basically what it was: White played a sideline (9.a3) which Black didn't properly know how to counter (he really needs to take on a3) and hence lost a tempo (...Bf8-e7xb4) which enabled White to put him into an inescapable bind. After which it was just a question of how to finish Black off, which he managed himself with a blunder (29...Rc7??) while his time was running short.

So it goes. But there's one thing that piques my curiosity. In the post-mortem, Das said that had I avoided the blunder on move 29 and played the better 29...Rf8, he was intending to play 30.Bxd5 Rxd5 31.Ree7 Rh5 32.g3, reaching the following position.

I wonder - is White actually winning this? Black's back is absolutely up against the wall, but how does White finish him off? I can't see any obvious way in which this can be done, assuming that the position is drawn if a pair of rooks are exchanged. I don't believe White can even get his king past the fourth rank, not without giving up his extra pawn. In which case isn't this a draw?

Maybe. I'd like to know. Or maybe I wouldn't. But it didn't happen that way, and I lost.

In the fourth round, both Angus and I were on 2/3 and were paired against grandmasters, and pretty strong ones at that: I had Black against Alexsander Delchev while Angus, on the next board, had White against the Hungarian David Berczes (2550) who is older than his photo here suggests.

Angus' notes (in italics) follow.

1.e4 e5 A surprise: I was expecting one of 1...c6, 1...c5 and 1...e6.

2.Nf3 Nc6

3.d4 exd4

4.Nxd4 Bc5

5.Nxc6 Qf6

6.Qf3 And a surprise for my opponent. [A 1...e5 player writes: this line is a pain in the behind when you're really trying to win - ejh]

6...Qxf3

7.gxf3 bxc6

8.Be3 Bb6 8...Bxe3 is more common.

9.Nd2 9.Rg1 Ne7 (also possible is 9...g6) 10.Rxg7?! Bxe3 11.fxe3 Ng6 12.Bc4 d5 13.exd5 Kf8 14.Rxg6 hxg6 15.dxc6 Rxh2 16.Nd2 Rh1+ 17.Nf1 with probably not enough compensation: -0.51 at 19-ply according to Houdini 1.5. Maybe 9.c4!? intending c5, even after 9...d6.

9...Ne7

10.O-O-O d6

11.Rg1 O-O

12.Nc4 Be6

13.f4 f5 13...d5? 14.f5

14.e5 d5

15.Nxb6 Better is 15.Na3, as my opponent suggested after the game.

15...axb6 I've "won" the bishop pair, but Black has mobile pawns and the a-file.

16.a3 c5

17.c3 c4

18.Be2 c5

19.Bf3 Rfd8 Here I decided that my position wasn't as good as it had been a little earlier I thought I wasn't going to get any play on the kingside and would have to wait for Black to play d4, after he'd prepared it by doubling rooks and playing the knight to b3.

20.Rd2 However, doubling rooks on the g-file, with 20.Rg3

and staying active was the right thing to do. This would also free d1 for the bishop to cover b3. Also Rg3 may provide useful defence along the third rank. The position is virtually equal according to Houdini.

20...Rd7

21.Rgd1 Rad8

22.Kc2 Nc6

23.Re2 d4

24.Ree1 dxe3

25.Bxc6 exf2

26.Bxd7 fxe1N+ 26...Bxd7 also works

White resigns

While this was going on, I was playing Delchev, who at 2622 may have been the highest-rated opponent I've ever faced (depending, I think, on what Tony Miles' grading was when I played him in December 1992).

The game did not begin auspiciously for me, since just before arriving at the playing hall I realised that I had no recollection at all of handing in my hotel room key at reception (which I had, in fact, done) and it was too late to go back and check. Then, fiddling around in my bag to see if I'd brought the key with me, I pulled out my right hand to find it covered in white stuff, which I thought at first was sun cream but which shortly proved itself to be Tippex from an inadvertently-opened bottle.

The subsequent cleaning-up operation was time-consuming as well as embarrassing, as I not only had to go through my bag to find what else had been covered in Tippex but had to make several trips to the toilets to try and wash off as much of it as possible - this after having tried to extend as much of my hand to Delchev, at the start of the game, as was possible without getting Tippex on him as well.

On top of this, I was still worrying about whether I had lost my room key, or left it in the door, leaving myself open to theft. This was a little distracting. It's fair to assume that neither of these two mini-disasters actually had an impact on the outcome of the game, but given that this was one of the biggest games of my life, I would have preferred that my concentration, never good at the best of times, had been a little less disturbed.

Anyway, on to the game, with Delchev playing White, and surprising me with the English Opening.

1.c4 I'd expected to play another Semi-Slav. But no matter.

1...Nf6

2.Nc3 e5

3.Nf3 Nc6

4.g3 Bb4

5.Bg2 O-O

6.O-O e4

7.Ng5 Bxc3

8.bxc3 Re8

9.f3 I used to play the White side of this, or I did theoretically, since I don't think I ever got this far down the line. I moved away from it because I liked it for Black: it never seemed to me to recover from the second game of the 1987 World Championship match in which Karpov surprised Kasparov with

9...e3 after which White's position never looked comfortable to me. However, that shouldn't lead anybody to conclude that I knew very much of the theory. I was confident I knew as far as move eleven for Black

10.d3 d5

11.Qb3 Na5 but from here on I was unsure. So after

12.Qa3 I continued

12...c6

13.cxd5 and now I wasn't clear with which piece I should take. The knight capture seemed more natural, but the more I looked at the pawn capture the more I preferred it, clearing c6 for my knight while obstructing e4 for his. So I played it. But the paradoxical outcome of so doing was that I was convinced that I had departed from theory and was therefore winging it - whereas, in fact, I was going straight down the main line!

13...cxd5

14.f4 Nc6 14...Bg4 is, I'm informed, generally preferred, but I don't have any reason to dislike the move I - and Karpov - played.

15.Rb1 b6 And here we depart from the original KvK game, in which Karpov played 15...Qc7, quite probably a better move than mine. 15...b6 has the apparent demerit of weakening the long diagonal, which Delchev of course saw, and attempted to take advantage. But he shouldn't have, because his sixteenth was a bad error, perhaps even, potentially, a game-losing one.

16.c4?

I thought for more than half-an-hour on the next move, which left me with barely more than ten minutes for the rest of the game (albeit I didn't, as it turned out, need very much more). I saw an idea, and its follow-up, and I was very tempted indeed to play it: but it seemed to me to be, probably, exciting but unsound. So, though I was, nevertheless, sorely tempted, I eventually decided that if I could find another move that looked both good and sound, I would play it. I did find another move: and though that move was sound enough, perhaps, in playing it, I missed my chance.

16...Bg4 This was the safe move. What the idea was, we'll see below.

17.Bb2 I didn't think of this: all I'd really considered was 17.Re1.

17...Bxe2

18.Rfe1 Bh5

19.cxd5?! The computer likes 19.Rbc1, strengthening the threat rather than rushing to the execution, though 19..Rc8 looks perfectly OK for Black. Now, however, I panicked, or whatever you want to call it: I thought that after 19...Nxd5 20.Qb3 Nce7 21.Ba3

I would be under intolerable pressure. But it's not so: after 21...Rc8 (and maybe even 21...h6 22.Ne4 Rc8, as the knight fork wins neither of the rooks) Black is at least fine.

However, I went instead for the desperate

19...Na5? and then after

20.Ne4 it's too late for

20...Nxd5? though 20...Nxe4 21.dxe4 is not a strategy for the long-term, either.

21.Nd6 Re6

22.Bxd5 Rxd6 and now my last hope was that 23.Bxa8 Rxd3 would give me a pawn or two and some long-diagonal compensation for the exchange, but he interposed

23.Qc3 and then noted that my attempt to play 23...f6 was an attempt to play an illegal move. Black will shortly have nothing for the exchange, and therefore

Black resigned.

But let us go back to the position after White's sixteenth.

The idea which I had, and on which I spent so much time before rejecting it, was 16...Nd4!

and then, after 17.Qb2, Black can play 17...Nf5, which I didn't consider, because I wanted to play the much more daring, and much stronger, 17...dxc4!!

Then, after White takes the rook with 18.Bxa8, I considered both 18...cxd3, which is not so strong, and 18...c3!, which certainly is.

Then, after 19.Qb4, Black naturally plays 19...Nxe2+ and then we have this position.

I hope you don't mind so many diagrams: I've provided them partly to strengthen the impression of an analysis proceeding several moves down the line, and yet not reaching the point of clarification. Which was partly my problem. It was unclear where I would go from here: indeed, everything was pretty much unclear, and I couldn't really convince myself that this position, which I thought about long and hard, was a mess in which I had good chances, rather than a mess in which I was probably going to be losing.

Part of the reason for this is that I was, perhaps understandably, looking for a way to play the c8 bishop somewhere strong in order to threaten to take the a8 bishop. But I couldn't see how it was to be done, and I wasn't convinced, and while at least once I was on the brink of reaching out and playing 16...Nd4 anyway, I didn't. I played the bishop move instead.

I wish I had gone with the knight. Although there are many different ways the game can go from here, I think Black has tremendous chances. It's far too complicated to analyse here, even if I had the time or the ability to do so, but White has two possible king moves here (20.Kg2 and 20.Kh1) after either of which Black has a number of options - but perhaps prime among them, either 20...h6 21.Ne4 Qxd3, or the immediate queen capture, 20...Qxd3. So for instance, after 20.Kg2 Qxd3

this looks like a massive position for Black. Already three pawns for a rook, and, more importantly, all sorts of attacking ideas. Perhaps there aren't many, or indeed any, one-move threats, and perhaps this too helps explain why I didn't really see how powerful my position was. But ask a computer, or try playing it yourself, and I think you'll find White's position is probably indefensible.

I'm sure, in practice, that I'd have been very lucky to win it, even had I reached it: five hundred Elo points is an awfully large gap in capability. Even so, I think I can be forgiven for regarding this one as a near-miss.

But a miss it was, near or otherwise. A miss is what it was.

[Das photo: Chessbase]

[Berczes photo: Ray Morris-Hill]

[Delchev photo: Chessdom]

[Thanks to Angus for notes]

During the first half, though, I played two grandmasters, while Angus, who was the best of our party with 6/10, played one. We scored, you'll not be astonished to hear, 0/3 in these games. But maybe it didn't have to be that way.

The first of these games was played in round two, in which I had the black pieces against Indian GM Neelotpal Das.

Not one of our victims at Benasque

At first sight it's a fairly straightforward stronger v weaker player crush, which is basically what it was: White played a sideline (9.a3) which Black didn't properly know how to counter (he really needs to take on a3) and hence lost a tempo (...Bf8-e7xb4) which enabled White to put him into an inescapable bind. After which it was just a question of how to finish Black off, which he managed himself with a blunder (29...Rc7??) while his time was running short.

So it goes. But there's one thing that piques my curiosity. In the post-mortem, Das said that had I avoided the blunder on move 29 and played the better 29...Rf8, he was intending to play 30.Bxd5 Rxd5 31.Ree7 Rh5 32.g3, reaching the following position.

I wonder - is White actually winning this? Black's back is absolutely up against the wall, but how does White finish him off? I can't see any obvious way in which this can be done, assuming that the position is drawn if a pair of rooks are exchanged. I don't believe White can even get his king past the fourth rank, not without giving up his extra pawn. In which case isn't this a draw?

Maybe. I'd like to know. Or maybe I wouldn't. But it didn't happen that way, and I lost.

In the fourth round, both Angus and I were on 2/3 and were paired against grandmasters, and pretty strong ones at that: I had Black against Alexsander Delchev while Angus, on the next board, had White against the Hungarian David Berczes (2550) who is older than his photo here suggests.

Not one of our victims at Benasque

Angus' notes (in italics) follow.

1.e4 e5 A surprise: I was expecting one of 1...c6, 1...c5 and 1...e6.

2.Nf3 Nc6

3.d4 exd4

4.Nxd4 Bc5

5.Nxc6 Qf6

6.Qf3 And a surprise for my opponent. [A 1...e5 player writes: this line is a pain in the behind when you're really trying to win - ejh]

6...Qxf3

7.gxf3 bxc6

8.Be3 Bb6 8...Bxe3 is more common.

9.Nd2 9.Rg1 Ne7 (also possible is 9...g6) 10.Rxg7?! Bxe3 11.fxe3 Ng6 12.Bc4 d5 13.exd5 Kf8 14.Rxg6 hxg6 15.dxc6 Rxh2 16.Nd2 Rh1+ 17.Nf1 with probably not enough compensation: -0.51 at 19-ply according to Houdini 1.5. Maybe 9.c4!? intending c5, even after 9...d6.

9...Ne7

10.O-O-O d6

11.Rg1 O-O

12.Nc4 Be6

13.f4 f5 13...d5? 14.f5

14.e5 d5

15.Nxb6 Better is 15.Na3, as my opponent suggested after the game.

15...axb6 I've "won" the bishop pair, but Black has mobile pawns and the a-file.

16.a3 c5

17.c3 c4

18.Be2 c5

19.Bf3 Rfd8 Here I decided that my position wasn't as good as it had been a little earlier I thought I wasn't going to get any play on the kingside and would have to wait for Black to play d4, after he'd prepared it by doubling rooks and playing the knight to b3.

20.Rd2 However, doubling rooks on the g-file, with 20.Rg3

and staying active was the right thing to do. This would also free d1 for the bishop to cover b3. Also Rg3 may provide useful defence along the third rank. The position is virtually equal according to Houdini.

20...Rd7

21.Rgd1 Rad8

22.Kc2 Nc6

23.Re2 d4

24.Ree1 dxe3

25.Bxc6 exf2

26.Bxd7 fxe1N+ 26...Bxd7 also works

White resigns

While this was going on, I was playing Delchev, who at 2622 may have been the highest-rated opponent I've ever faced (depending, I think, on what Tony Miles' grading was when I played him in December 1992).

Not one of our victims at Benasque

The game did not begin auspiciously for me, since just before arriving at the playing hall I realised that I had no recollection at all of handing in my hotel room key at reception (which I had, in fact, done) and it was too late to go back and check. Then, fiddling around in my bag to see if I'd brought the key with me, I pulled out my right hand to find it covered in white stuff, which I thought at first was sun cream but which shortly proved itself to be Tippex from an inadvertently-opened bottle.

The subsequent cleaning-up operation was time-consuming as well as embarrassing, as I not only had to go through my bag to find what else had been covered in Tippex but had to make several trips to the toilets to try and wash off as much of it as possible - this after having tried to extend as much of my hand to Delchev, at the start of the game, as was possible without getting Tippex on him as well.

On top of this, I was still worrying about whether I had lost my room key, or left it in the door, leaving myself open to theft. This was a little distracting. It's fair to assume that neither of these two mini-disasters actually had an impact on the outcome of the game, but given that this was one of the biggest games of my life, I would have preferred that my concentration, never good at the best of times, had been a little less disturbed.

Anyway, on to the game, with Delchev playing White, and surprising me with the English Opening.

1.c4 I'd expected to play another Semi-Slav. But no matter.

1...Nf6

2.Nc3 e5

3.Nf3 Nc6

4.g3 Bb4

5.Bg2 O-O

6.O-O e4

7.Ng5 Bxc3

8.bxc3 Re8

9.f3 I used to play the White side of this, or I did theoretically, since I don't think I ever got this far down the line. I moved away from it because I liked it for Black: it never seemed to me to recover from the second game of the 1987 World Championship match in which Karpov surprised Kasparov with

9...e3 after which White's position never looked comfortable to me. However, that shouldn't lead anybody to conclude that I knew very much of the theory. I was confident I knew as far as move eleven for Black

10.d3 d5

11.Qb3 Na5 but from here on I was unsure. So after

12.Qa3 I continued

12...c6

13.cxd5 and now I wasn't clear with which piece I should take. The knight capture seemed more natural, but the more I looked at the pawn capture the more I preferred it, clearing c6 for my knight while obstructing e4 for his. So I played it. But the paradoxical outcome of so doing was that I was convinced that I had departed from theory and was therefore winging it - whereas, in fact, I was going straight down the main line!

13...cxd5

14.f4 Nc6 14...Bg4 is, I'm informed, generally preferred, but I don't have any reason to dislike the move I - and Karpov - played.

15.Rb1 b6 And here we depart from the original KvK game, in which Karpov played 15...Qc7, quite probably a better move than mine. 15...b6 has the apparent demerit of weakening the long diagonal, which Delchev of course saw, and attempted to take advantage. But he shouldn't have, because his sixteenth was a bad error, perhaps even, potentially, a game-losing one.

16.c4?

I thought for more than half-an-hour on the next move, which left me with barely more than ten minutes for the rest of the game (albeit I didn't, as it turned out, need very much more). I saw an idea, and its follow-up, and I was very tempted indeed to play it: but it seemed to me to be, probably, exciting but unsound. So, though I was, nevertheless, sorely tempted, I eventually decided that if I could find another move that looked both good and sound, I would play it. I did find another move: and though that move was sound enough, perhaps, in playing it, I missed my chance.

16...Bg4 This was the safe move. What the idea was, we'll see below.

17.Bb2 I didn't think of this: all I'd really considered was 17.Re1.

17...Bxe2

18.Rfe1 Bh5

19.cxd5?! The computer likes 19.Rbc1, strengthening the threat rather than rushing to the execution, though 19..Rc8 looks perfectly OK for Black. Now, however, I panicked, or whatever you want to call it: I thought that after 19...Nxd5 20.Qb3 Nce7 21.Ba3

I would be under intolerable pressure. But it's not so: after 21...Rc8 (and maybe even 21...h6 22.Ne4 Rc8, as the knight fork wins neither of the rooks) Black is at least fine.

However, I went instead for the desperate

19...Na5? and then after

20.Ne4 it's too late for

20...Nxd5? though 20...Nxe4 21.dxe4 is not a strategy for the long-term, either.

21.Nd6 Re6

22.Bxd5 Rxd6 and now my last hope was that 23.Bxa8 Rxd3 would give me a pawn or two and some long-diagonal compensation for the exchange, but he interposed

23.Qc3 and then noted that my attempt to play 23...f6 was an attempt to play an illegal move. Black will shortly have nothing for the exchange, and therefore

Black resigned.

But let us go back to the position after White's sixteenth.

The idea which I had, and on which I spent so much time before rejecting it, was 16...Nd4!

and then, after 17.Qb2, Black can play 17...Nf5, which I didn't consider, because I wanted to play the much more daring, and much stronger, 17...dxc4!!

Then, after White takes the rook with 18.Bxa8, I considered both 18...cxd3, which is not so strong, and 18...c3!, which certainly is.

Then, after 19.Qb4, Black naturally plays 19...Nxe2+ and then we have this position.

I hope you don't mind so many diagrams: I've provided them partly to strengthen the impression of an analysis proceeding several moves down the line, and yet not reaching the point of clarification. Which was partly my problem. It was unclear where I would go from here: indeed, everything was pretty much unclear, and I couldn't really convince myself that this position, which I thought about long and hard, was a mess in which I had good chances, rather than a mess in which I was probably going to be losing.

Part of the reason for this is that I was, perhaps understandably, looking for a way to play the c8 bishop somewhere strong in order to threaten to take the a8 bishop. But I couldn't see how it was to be done, and I wasn't convinced, and while at least once I was on the brink of reaching out and playing 16...Nd4 anyway, I didn't. I played the bishop move instead.

I wish I had gone with the knight. Although there are many different ways the game can go from here, I think Black has tremendous chances. It's far too complicated to analyse here, even if I had the time or the ability to do so, but White has two possible king moves here (20.Kg2 and 20.Kh1) after either of which Black has a number of options - but perhaps prime among them, either 20...h6 21.Ne4 Qxd3, or the immediate queen capture, 20...Qxd3. So for instance, after 20.Kg2 Qxd3

this looks like a massive position for Black. Already three pawns for a rook, and, more importantly, all sorts of attacking ideas. Perhaps there aren't many, or indeed any, one-move threats, and perhaps this too helps explain why I didn't really see how powerful my position was. But ask a computer, or try playing it yourself, and I think you'll find White's position is probably indefensible.

I'm sure, in practice, that I'd have been very lucky to win it, even had I reached it: five hundred Elo points is an awfully large gap in capability. Even so, I think I can be forgiven for regarding this one as a near-miss.

But a miss it was, near or otherwise. A miss is what it was.

[Das photo: Chessbase]

[Berczes photo: Ray Morris-Hill]

[Delchev photo: Chessdom]

[Thanks to Angus for notes]

Thursday, July 21, 2011

Con un poco de suerte

I'm not sure how Spanish chessers would say, "It was a tournament of two halves, Brian", but however they'd do it, it would be a pretty good description of my ten days in Benasque. Rounds one to five and six to ten were so different for me that I could easily have been playing two entirely separate five game Swisses: a brace of tournaments-within-a-tournament, which, as it happens, were divided by an incredible dollop of good fortune.

I don't really believe in luck as far as chess is concerned. Often when I hear people talking about being unlucky, or, more rarely, the reverse, it sounds to me that what they're actually describing are patterns that they cannot, or will not, see. Anyhoo, since by definition luck is something outside of our control there doesn't seem to be much point in devoting our time to it - as opposed to thinking about what we can do to give ourselves a better chance of being lucky and how we can minimise the likelihood of suffering accidents, I mean.

Luck does exist, of course - those amongst our esteemed readership who are of a slightly older vintage may recall how Jonathan Speelman's second's girlfriend happening to buy a newspaper on her way from Norway to London had a decisive impact on his Candidates' match with Short in 1988 - but it evens out in the long run and, clearly, it's what we do with the chances that come our way, deserved or otherwise, that matters. At some point I'll get around to blogging about this in the context of an individual game (specifically, the 4th round of Sunningdale in May), but today I'll stick to how a chance event can, and did, turn the course of an entire tournament.

It was not, by any stretch of the imagination, what you might call a good start. After losing in the first round I won by default in the second, got duffed up in short order by a 2470 in round three and drew against a lower-rated opponent in round four. This last game was certainly not a gimme, but, at 1840-odd, she was in a range against which I've scored pretty well in the season just gone and I was annoyed with myself that I didn't win.

Including my games from Gatwick in June I was now nine without a win and my measly 1.5/4 was lacking a good deal of lustre. I think it's fair to say that I was lacking a bit of confidence when I sat down to face my fifth-round opponent, a local man rated in the 1820s.

I was Black and after 22 not hugely interesting moves, we arrived here.

This looks like the sort of thing that you'd expect to get playing blitz on the internet against modestly graded opposition. Breaking open White's position might not be entirely straightforward, but it's hard to imagine how Black could possibly get into trouble from here. I managed it, though.

My last move before the diagram position was 21 ... a6 and I remember thinking before playing it that sooner or later White would go a3-a4 and b4-b5 and I'd have to respond with ... axb5 otherwise he'd swap off and I'd be left with a pawn on a6 that I wouldn't be able to defend. When it came to it, however, I jiggered things up by playing my moves in the wrong order.

Around fifteen moves later, I had a long think and calculated a line that went

That, at least, was what my head decided to do. My hand, however, had other ideas and pushed my king forward forgetting to swap pawns first. FECK!!!

I spent the next few moves debating whether I should stab my own eyes out with a spare bishop or simply do the world a favour and go hurl myself off a mountain (there being quite a few to choose from in the immediate vicinity). Then, in this position,

White unaccountably played 45 Rb2.

That, dear reader, is how I managed to win my first game in Benasque. It was a ridiculous win, for sure, but one which completely transformed my tournament nonetheless. After struggling to hit a cow's arse with a banjo during the first five days, I went on to score 50% against opponents with an average rating in the 2080s (180 ECF, give or take) over the last five and that, as Justin kindly mentioned on Monday, turned out to be enough for me to win the trophy for the 'Best score by a player without an elo rating' prize and the 200 euros that went with it*.

Uploaded to Youtube by 'Hot4Kylie'.

One feels this is unlikely to be whoever it was that put up all those Master Games

Was I just hugely lucky, then? Well, I was very fortunate, in the sense that if my opponent in this game hadn't blundered the rook I'm quite sure that my tournament as a whole would have ended very differently, but, even so, I don't think it was just luck.

Yes, I was fortunate to get the opportunity in the first place - we could probably play another hundred games without my opponent playing a move like 45 Rb2 again - but I still had to play well in the following rounds (or better than I usually do, at least) to make use of the chance I was given.

What's Spanish for "You make your own luck in this game"? Whatever it is, I'd rather like it as my motto, but a helping hand every now and is never unwelcome.